Predictive Modeling of Transmitted Wavefront Error in High-Performance Optical Coatings

Alluxa Engineering Team

An analytical approach to predicting coating-contributed surface error when measurement is limited or inadequate.

Introduction

Modern optical systems increasingly demand tighter tolerances, higher throughput, and greater consistency across larger apertures. As these performance requirements grow, so does the need to understand—and confidently control—the factors that degrade optical wavefront quality. Among these factors, Transmitted Wavefront Error (TWE) remains one of the most critical, yet most frequently misunderstood, contributors to system level performance.

TWE quantifies how much an optical element distorts the wavefront of a light wave as it propagates through the component. In an ideal system, a plane wave should emerge from a filter or window without any change in phase front. In practice, however, real optical components introduce non-ideal phase variations or errors from sources such as coating thickness gradients, substrate shape, internal material inhomogeneity, or the interaction of multiple surfaces. These variations/errors can reduce image fidelity, shift focal positions, and introduce aberrations into the optical system.

Circumstances can render it infeasible to empirically measure TWE. A combination of coating properties, wavelength limitations, and instrument constraints can interfere with measurement; still, demonstrating compliance remains essential. To address this challenge, Alluxa’s engineering team has developed an analytical framework for predicting TWE when direct interferometric measurement is impractical or when cost and equipment limitations prohibit full characterization. This predictive modeling approach—based on spectral uniformity—is showcased as a way to estimate coating-contributed TWE with high confidence when direct measurement is not an option.

TWE Discussion

Transmitted Wavefront Error is the industry metric used to quantify the distortion imparted onto a light wave as it passes through an optical component, such as a filter, lens, or window. In an idealized optical system, a plane wavefront entering a flat component should emerge as an unaltered plane wavefront.

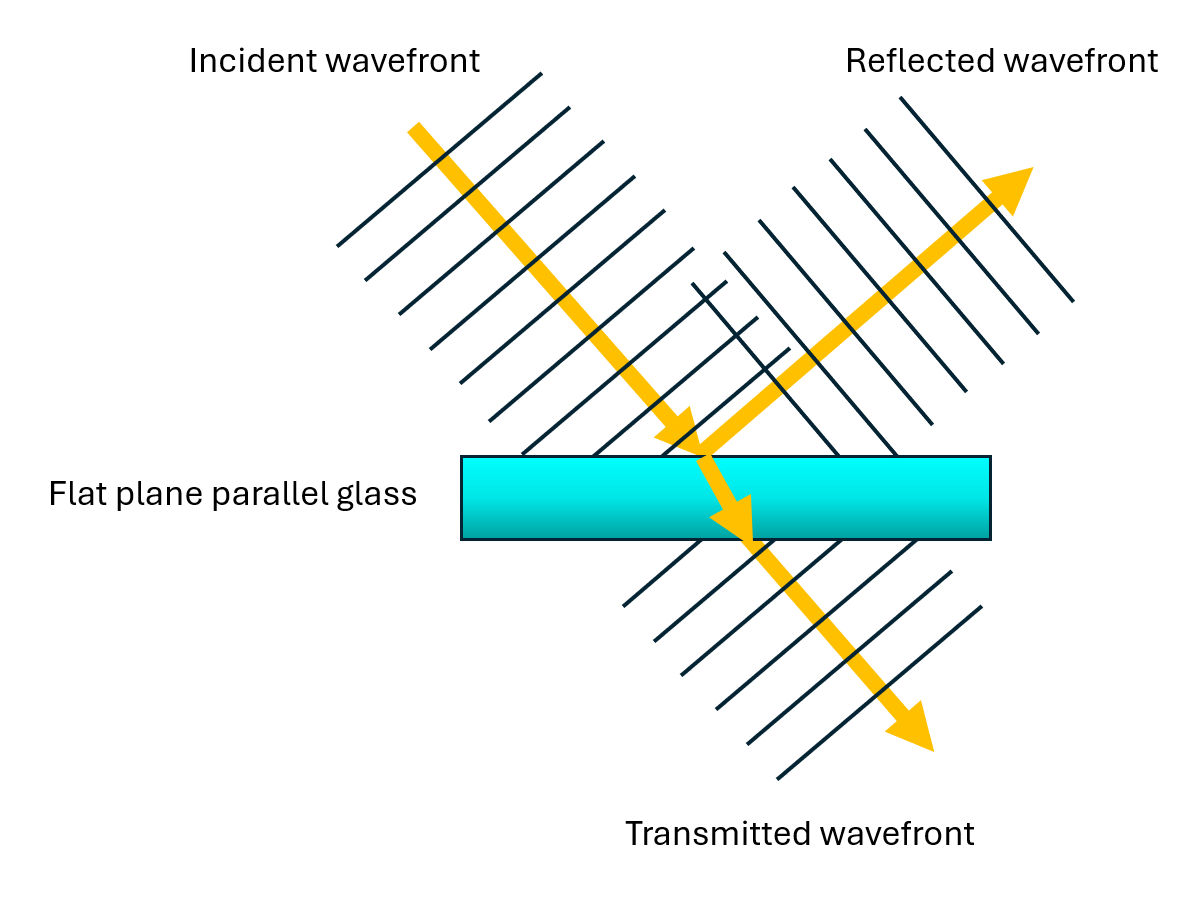

Figure 1a. Light beam wavefront transmitted and reflected by a perfectly flat plane parallel transparent substrate.

Figure 1b. Light beam wavefront transmitted and reflected by the same glass substrate after bending introduces curvature to the surfaces.

However, in practice, essentially all wavefronts deviate from this ideal shape. TWE measures the difference between the emerging wavefront and the ideal reference wavefront.

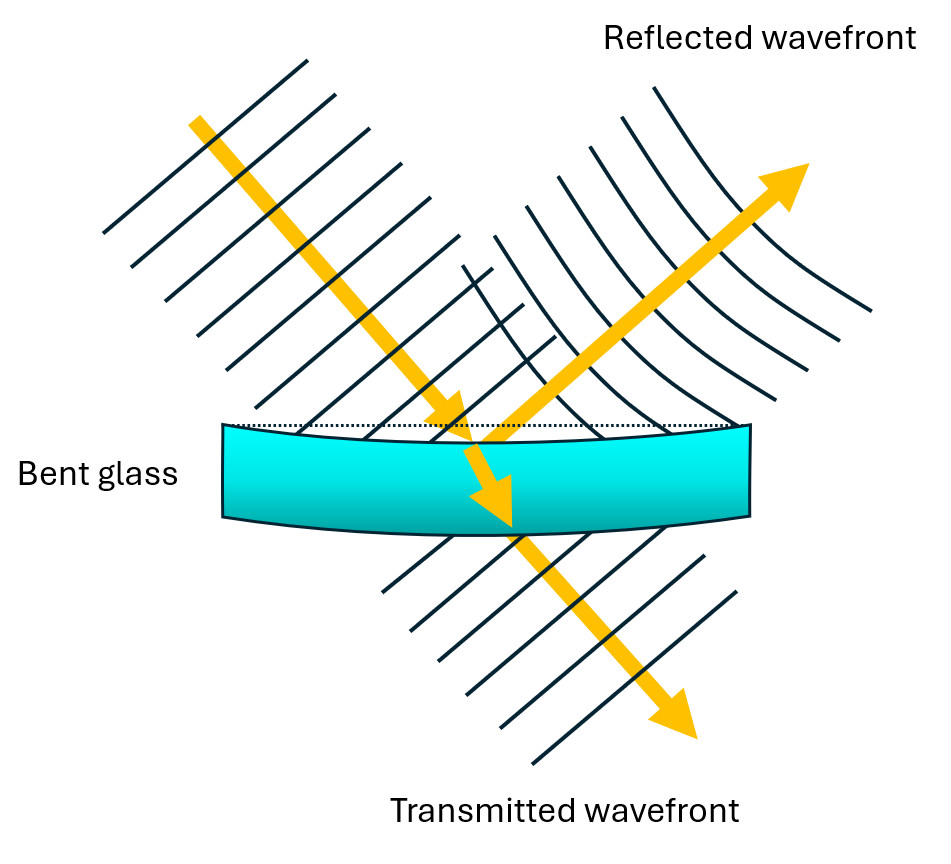

As a metric, TWE does not typically include all distortions experienced by a wavefront traveling through an optical component. Piston, tilt and power (Figure 2) are typically not included in the final TWE value. The reasons for this exclusion are:

- Piston simply represents a uniform shift in the phase of the entire wavefront along the axis of propagation. Although this can sometimes be important, in most standalone imaging or filtering applications, piston can be ignored because it does not change the shape of the wavefront or the quality of the image; it simply shifts the absolute phase, which neither the human eye nor standard sensors can detect.

- Tilt occurs when the wavefront arrives at an angle relative to the optical axis. It can be caused by thickness variation in a part, such as a physical wedge in a substrate, or by misalignment within the system. Tilt does not introduce blur and can often be corrected in system alignment by adjusting a mirror or realigning a sensor.

- Power is a rotationally symmetric curvature of the wavefront, causing a plane wave to converge or diverge, effectively acting like a weak lens. Although this aberration can be critical in fixed-focus systems, in systems with adjustable focus, this can typically be compensated and is therefore excluded from the total contributed wavefront distortion.

Figure 2. Total wavefront distortion is the sum of piston, tilt and power components in addition to irregularity. TWE always includes irregularity and sometimes power but rarely piston or tilt.

While distortions on reflection —referred to as Reflective Wavefront Error (RWE)—can also be important, the focus here is on TWE. RWE is distinctly different from TWE. For example, reflection from a slightly bent, plane parallel substrate (Figure 1b) will show curvature in the reflected wavefront, while the transmitted wave remains nearly unaffected aside from a small tilt.

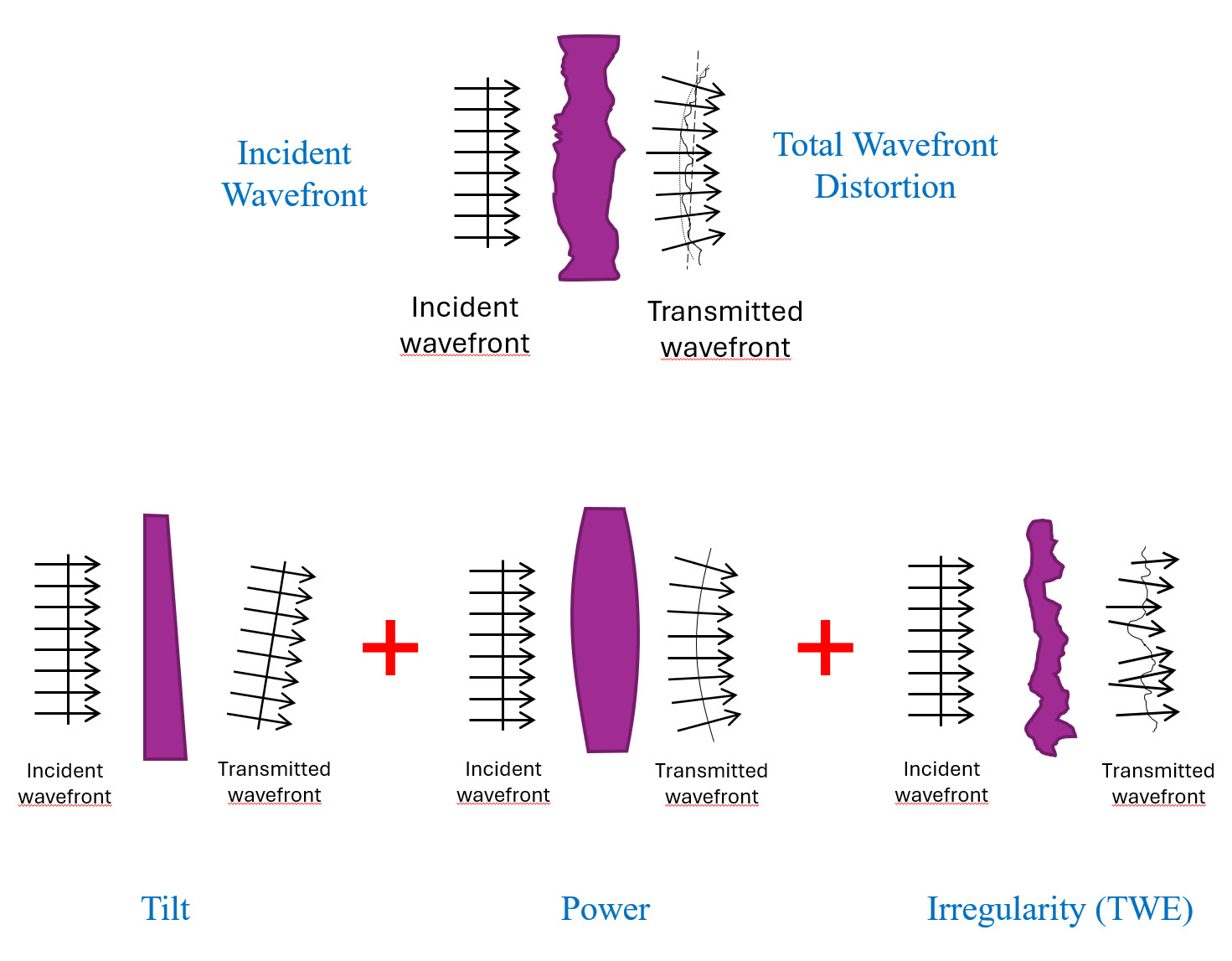

One common misconception when specifying wavefront error is the assumption that surface flatness directly correlates to TWE. However, the individual flatness contributions from the two surfaces alone cannot reliably predict transmitted wavefront error. Surface geometries of an optical flat may either cancel or compound distortions. If the aspect of one surface matches that of the other surface, TWE can be minimal (Figure 3b). If they are similar but noncomplementary, TWE can double (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Transmitted wavefront distortion for a) flat substrate, b) substrate non-flat in the same way on both sides, c) substrate with the same non-flat top and bottom surfaces as in b) but with the bottom surface flipped.

Determining TWE from Wavelength Uniformity

TWE is determined solely by the change in the transmitted wavefront, i.e., the relative changes in phase at different positions across the clear aperture of the optical component. Interferometry is the standard method for measuring TWE, as it directly maps wavefront phase. This method is not always practical, though, since interferometric measurements can be compromised by ghost reflections, alignment errors, or where the optic is opaque at the interferometer’s source wavelength.

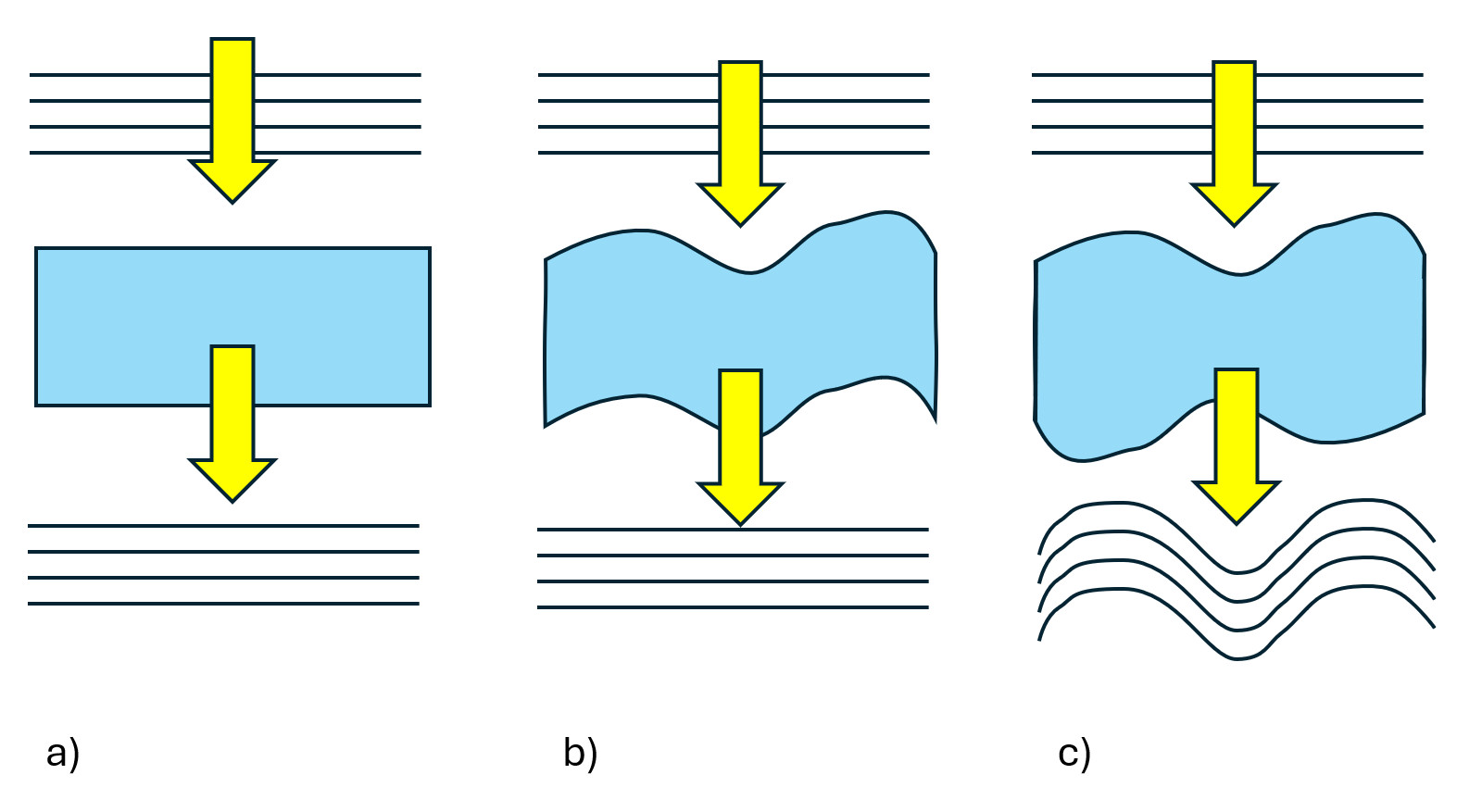

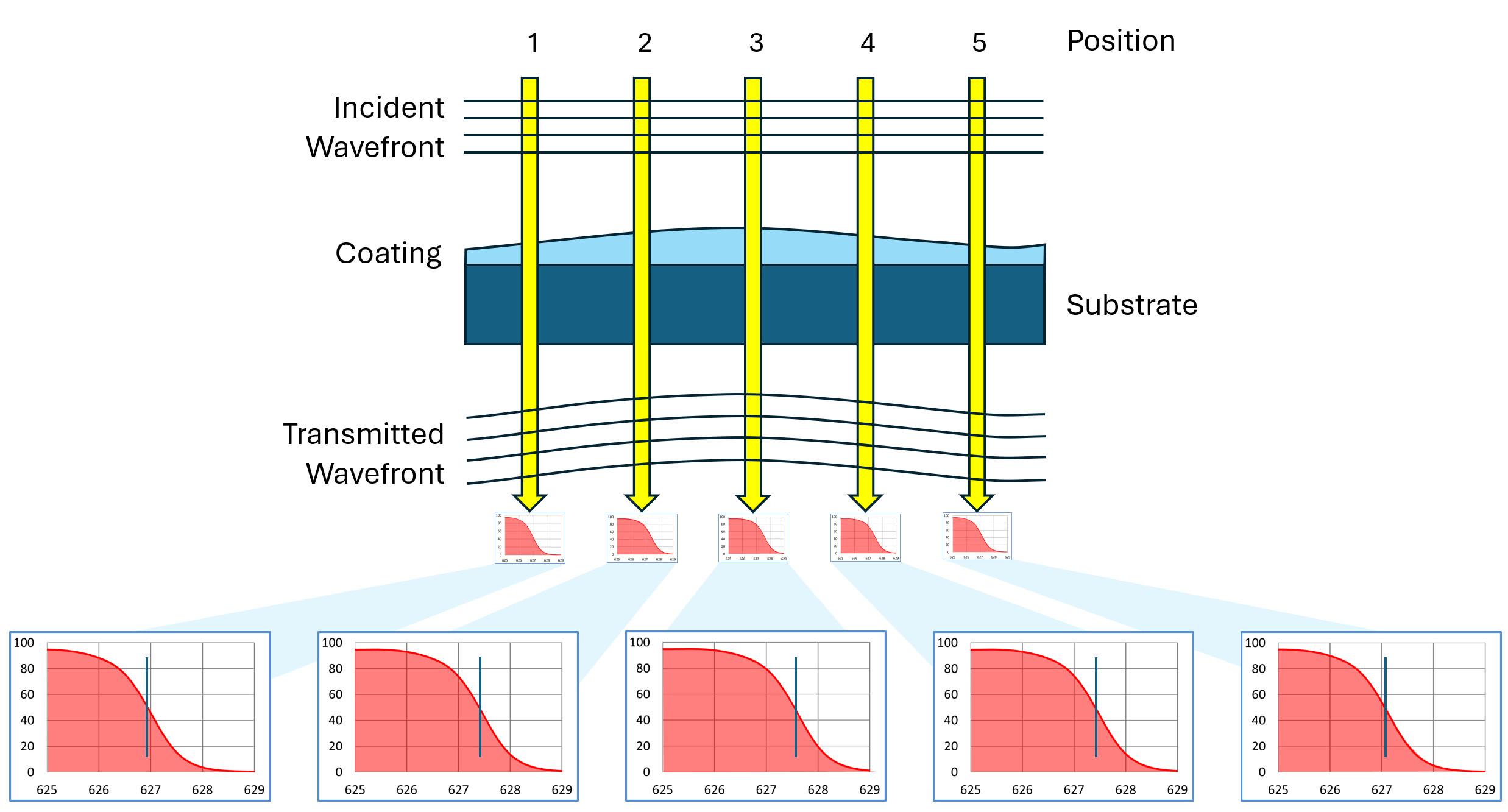

For cases where interferometry is impractical, TWE can be determined analytically. The analysis can be done using wavelength uniformity measurements over the working clear aperture of the filter. A change in coating thickness, i.e. non-uniformity, leads to a proportional change in optical phase thickness. Considering this relationship, wavelength shifts can be converted directly into TWE (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Phase shifts in an incident wavefront after transmission through a filter with variations in coating thickness across the surface. Wavelength dependent features appear at longer wavelengths in areas with thicker coating.

This method relates coating thickness and spectral position to changes in phase across the part. The approach relies on some relatively easy-to-satisfy requirements driven by the coating process itself.

The first requirement is the dominance of the coating thickness as the principal source of wavefront distortion. Wavelength variations across the clear aperture should be driven solely by coating thickness, and influence from the substrate or other factors should be negligible. The second is that the layer thicknesses should scale proportionally across the part. To a first order approximation, all layers in the coating stack should increase or decrease in thickness together. Third, the thickness changes of each layer should be small relative to the layer thickness. This ensures any shift is only a slight change in phase and, consequently, can be determined to sufficient accuracy using a first order approximation. Finally, the thickness variations should occur gradually across the surface. This reduces the total number of measurements required to characterize the entirety of the part and allows for each measurement to be made over a reasonable area.

These requirements are typically satisfied by precision PVD coating processes such as evaporation and sputtering. During the coating process, slight variations in thickness are inevitable due to the variation in deposition thickness throughout a coating chamber. As coating thickness increases, spectral features shift to longer wavelengths; when thickness decreases, they shift shorter.

The transmission curve of a thin-film filter is shaped by interference between layers and is extremely sensitive to layer thickness. Subnanometer variations can noticeably distort the spectral response curve. To enable the use of spectral performance as a measurement of TWE, the spectral curve should closely match the expected theoretical curve, with minimal distortion. For the analysis to be effective, the spectral non-uniformity should manifest in a first order shift in overall wavelength position; more complicated variations in the layer-to-layer thickness impacting the final spectral curve would render this proposed method inaccurate. For high-layer count coatings with precise wavelength features, if the spectral curve retains its shape and matches the theoretical model, this provides confidence that the thickness change is small relative to the layer thickness. Then, the wavelength shifts can be modeled as a constant percentage change in coating thickness.

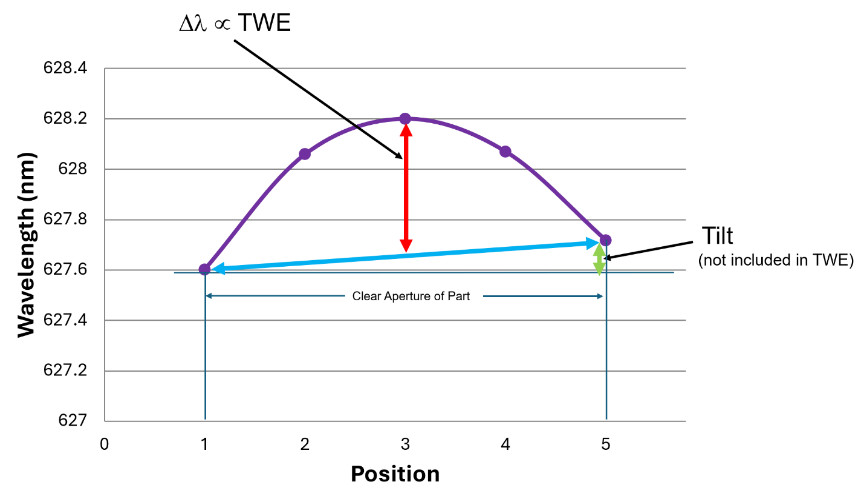

Once the integrity of the spectral shape is determined, the process to calculate TWE can be summarized as follows. A spectrophotometer or a laser/detector system measures a specific or unique spectral feature (such as a 50% edge or peak wavelength) at multiple points across the aperture. These measurements are plotted in the form of wavelength shifts as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Measured wavelength variation vs. position. A part which has a wavelength dependence as shown by the purple curve, has a maximum wavelength variation, for TWE purposes, shown by the red arrow. This is less than the maximum change in wavelength across the part, as the linear drift in wavelength, shown by the blue line and green arrow, is ignored. This is because a linear change in wavelength, corresponding to a linear change in thickness or phase, only introduces tilt to the wavefront, and tilt isn’t included as part of the TWE metric.

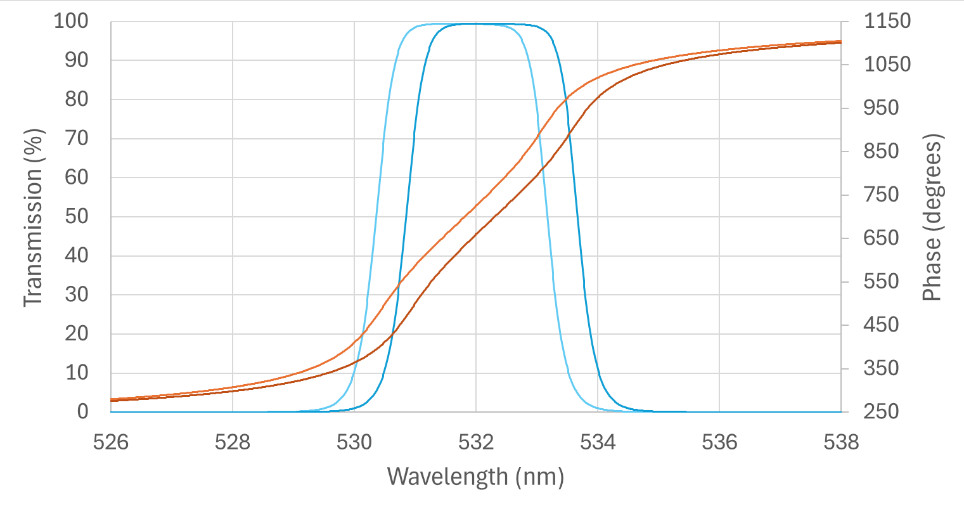

The wavelength shifts are translated into a final max shift value for phase or TWE. The phase change for a single layer is a simple product of refractive index ‘n’ and thickness ‘d’. However, for multi-layer stacks it is necessary to use complex thin-film modeling programs to calculate the appropriate scale factor. This is illustrated in Figure 6, which shows theoretical transmission and phase for an example case of a 532 nm bandpass filter.

Figure 6. Transmission amplitude and phase for a 532nm bandpass filter. The two curves are identical filters but with a difference in thickness of 0.1%. This results in a phase change at 532nm of about 65 degrees for the wavelength shift of ~0.49 nm shown.

In this example, a thickness change of 0.1% was modeled using an industry standard thin-film design program. A 0.1% thickness increase was introduced and the resulting wavelength shift of +0.49 nm is clear and is seen both in the transmission curve and the phase curve. This calculated phase change provides the scale factor needed to relate a given wavelength shift to a given phase change. Note the phase change, and thus TWE value, is small in wavelength regions where the transmission is low, but is easily determined for wavelengths near the passband. At the center wavelength of 532 nm the shift of +0.49 nm results in a phase change of +65 degrees. Thus, for this wavelength the scale factor converting wavelength shift to TWE would be 65/360, the phase change as a fraction of a full wave, divided by 0.49, the wavelength shift producing that phase change, for a final value of 0.37, which is termed the “phase wavelength”. Since TWE is typically expressed in waves, similarly to flatness, the TWE value would be one over this value, or λ/2.7 waves.

In summary, a uniform percentage thickness change across all layers allows the manufacturer to use a design’s theoretical wavelength sensitivity to convert measured spectral shifts into accurate, though still approximate, TWE values. As will be demonstrated in the following section, this approximation is often conservative.

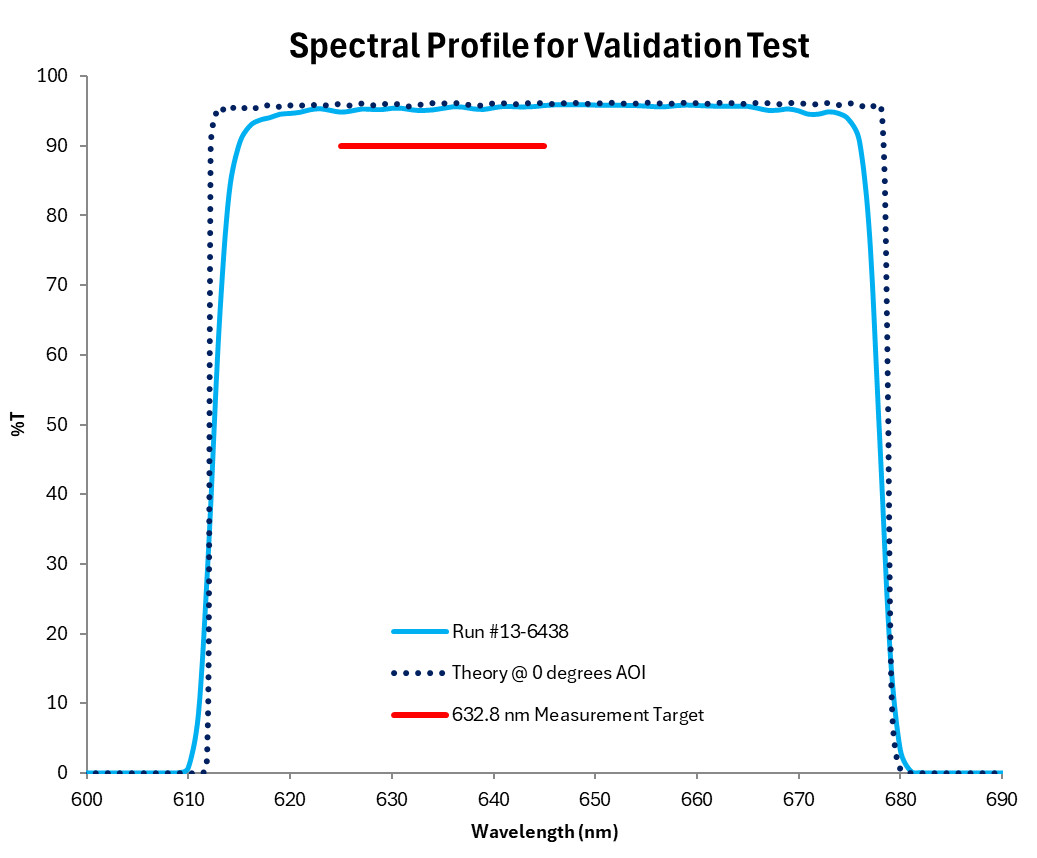

Validation A: Linear Fit Model

To validate the model, a 3” diameter substrate with tightly controlled TWE was pre-measured to characterize the surface error sans coating. A custom thin-film bandpass filter was designed with a threefold objective: to optimize transmission at the Zygo Verifire’s 632.8 nm measurement line, to contain an easy-to-reference feature such as an edge, and to maximize the phase wavelength factor. The design was deposited on the pre-characterized substrate with the result showing a wavelength dependence seen in Figure 7, with the goal of producing measurable non-uniformity across the part.

Figure 7. Transmission profile for thin-film validation design, measured on the HELIX spectral analysis instrument with ~F/10 divergence.

Spectral measurements were performed at 9 different positions along a line across a ~67 mm clear aperture. A spectral non-uniformity of ~1.5% facilitated the separation of the distinct edge features.

The same part was then measured using an interferometer. A measurement clear aperture of 68.5 mm provided a direct comparison with the analytical wavelength-shift derived TWE estimate.

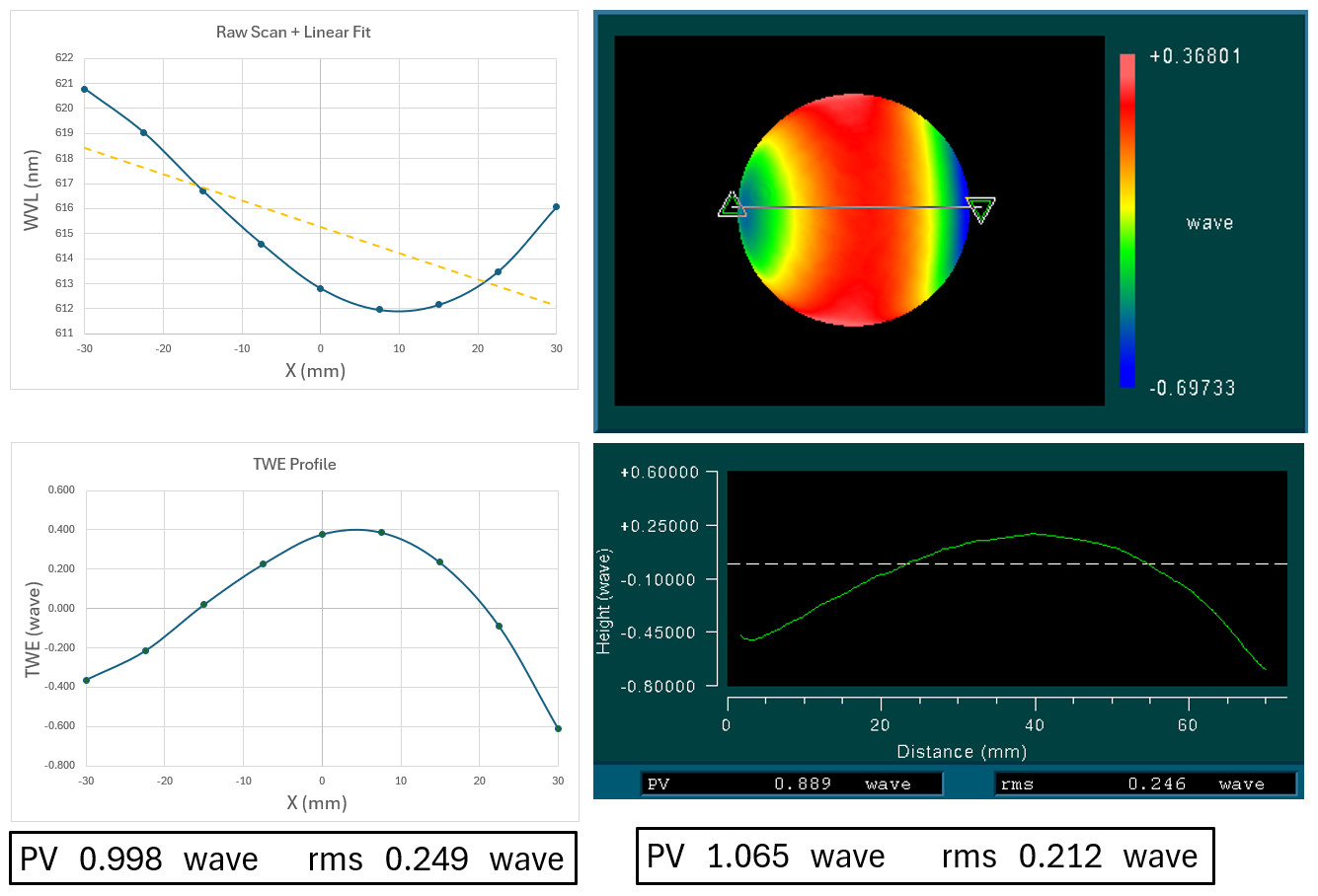

On the right side of Figure 8, the empirical phase change across the part measured by the interferometer is shown both as a heat map and a selected cross-section. The left side depicts the transmission measurements of the 50% edge wavelengths of the bandpass along with a simple linear fit to the data. The linear fit allows a tilt-correction of the raw data. The resulting values are then multiplied by the phase wavelength factor, obtained from the design software, to determine the final TWE values.

Figure 8. Comparison of TWE values found using analytic TWE calculations compared to values seen using interferometer measurements.

The final TWE values obtained both analytically and interferometrically are shown in the boxes at the bottom of the figure. As seen, the Peak-to-Valley (P-V) values are similar, within ~6%. The Root Mean Square (RMS) correlation is less strong but can be attributed to using a 4:1 PV-to-RMS conversion ratio, consistent with an optomechanical rule-of-thumb[1].

Validation B: RMSt Grid Method

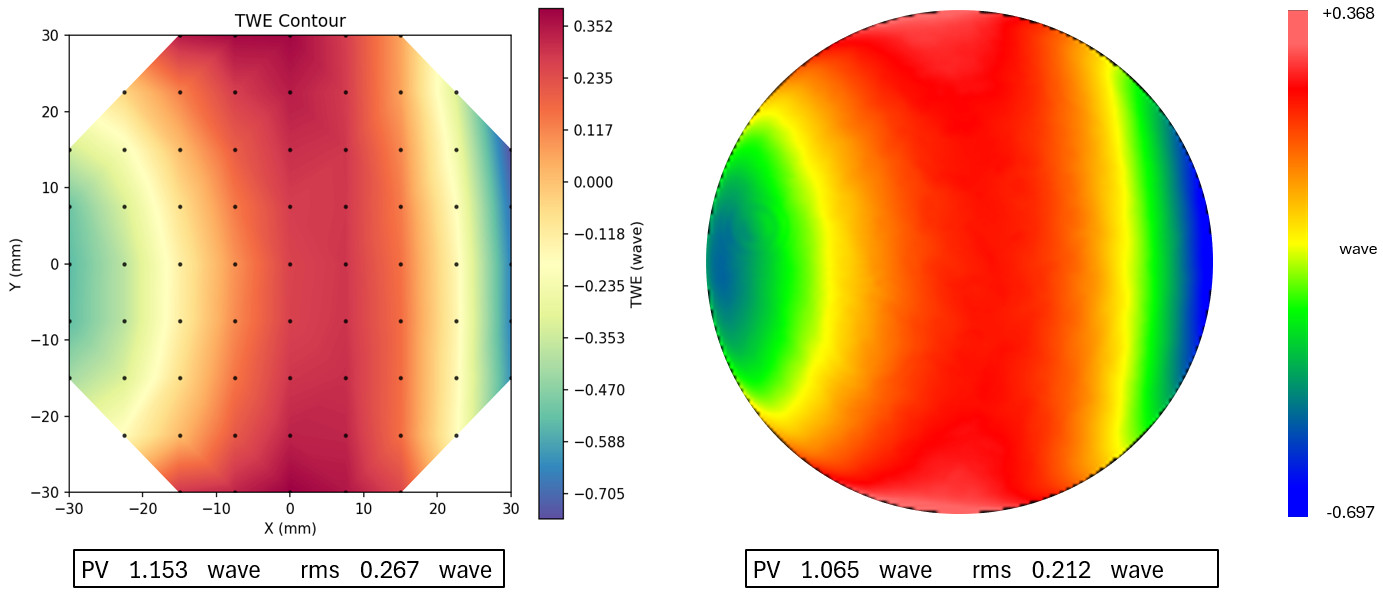

An alternate method to calculate TWE uses a grid to evaluate the RMS of TWE values across the entire surface rather than just a single cross section. This determines directly from transmission wavelength variations. This method is typically reserved for higher-value optics where the extra cost of increased spectral scans can be justified. An order of magnitude more scans (70 versus 9) are required to provide sufficient point density to evaluate TWE over the entire surface.

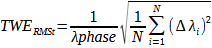

The TWE is calculated using the following equation:

Equation 1. Equation for calculating grid-method TWE.

Where,

- is the phase wavelength of the optical filter stack

- Δλi is the CWL or 50% edge point deviation from average

- N is the number of scan points

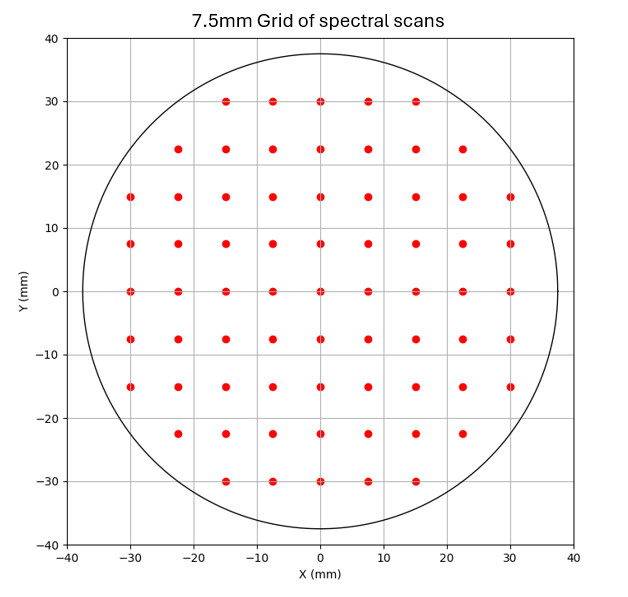

In this example a grid of spectral scan points is taken over the clear aperture of the part.

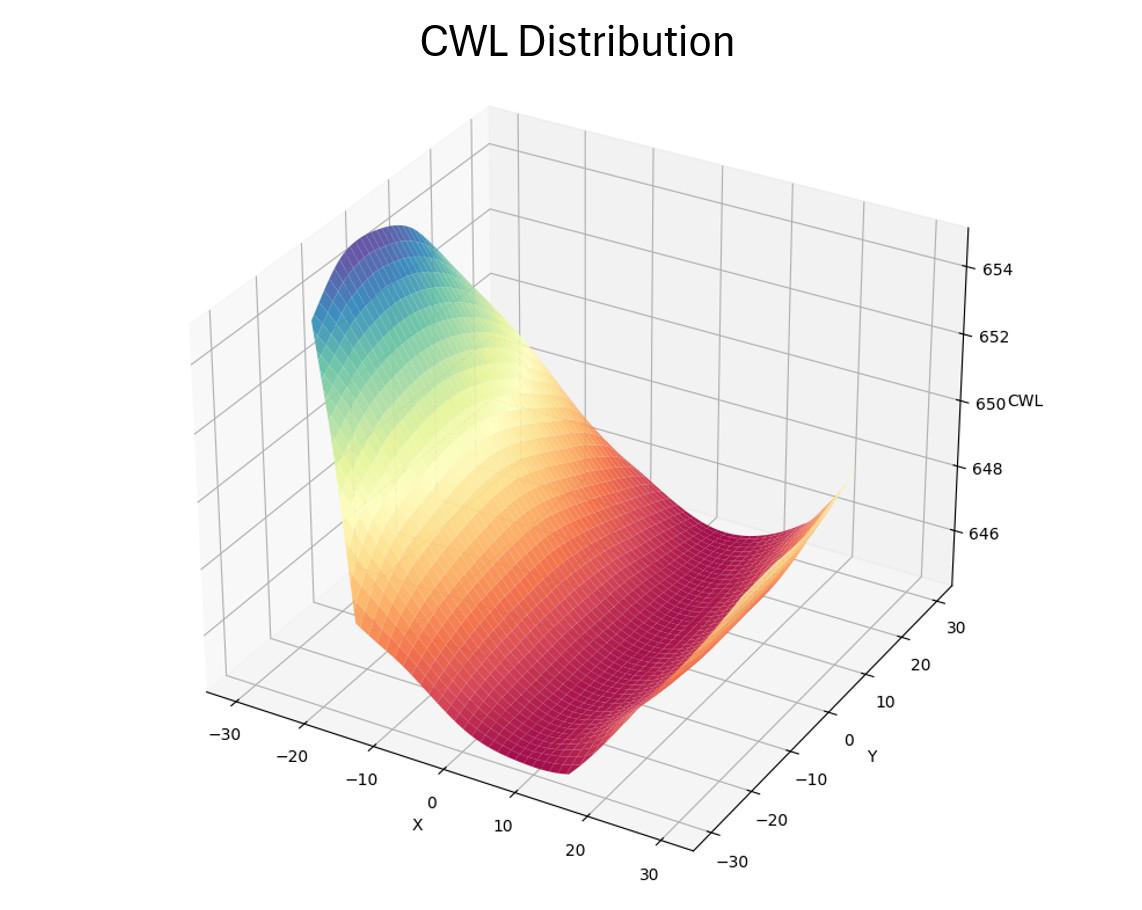

The CWL or 50% edge points for each scan is calculated and arranged into a data table visualized here:

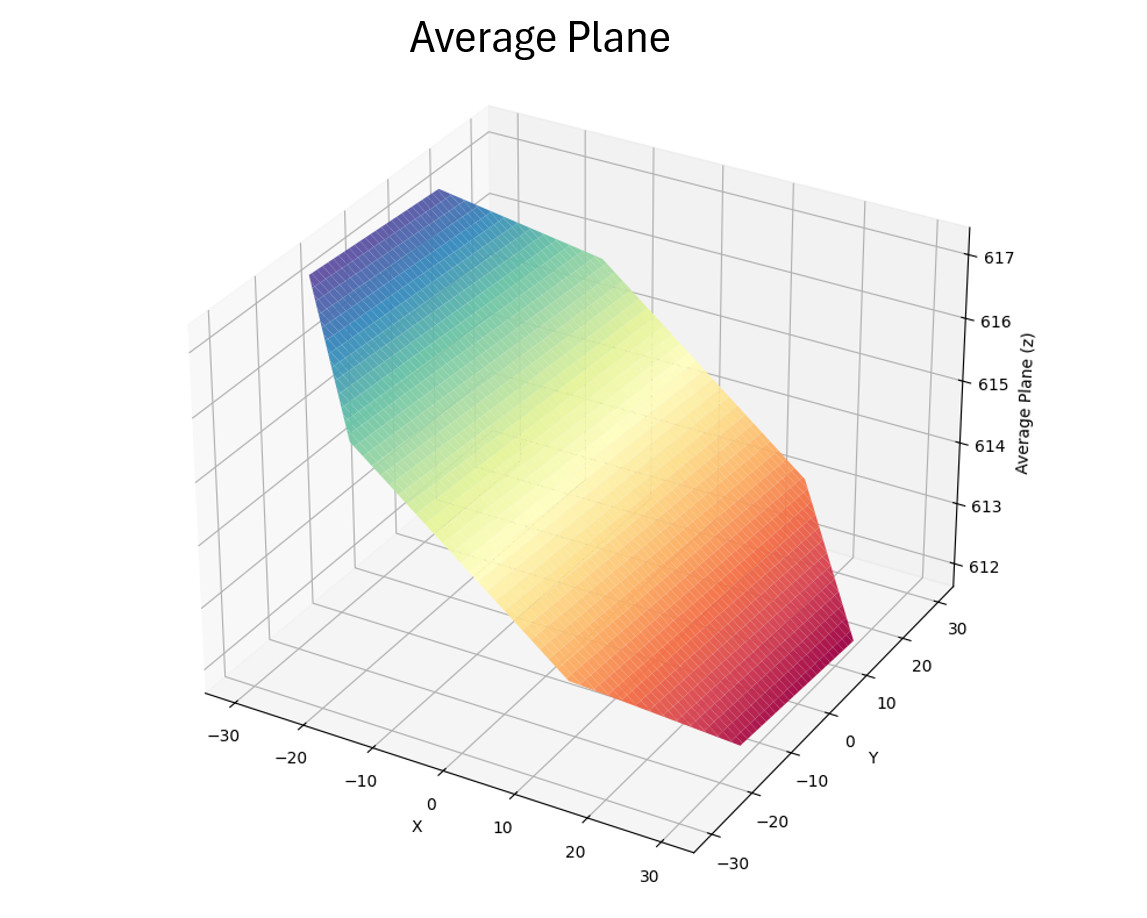

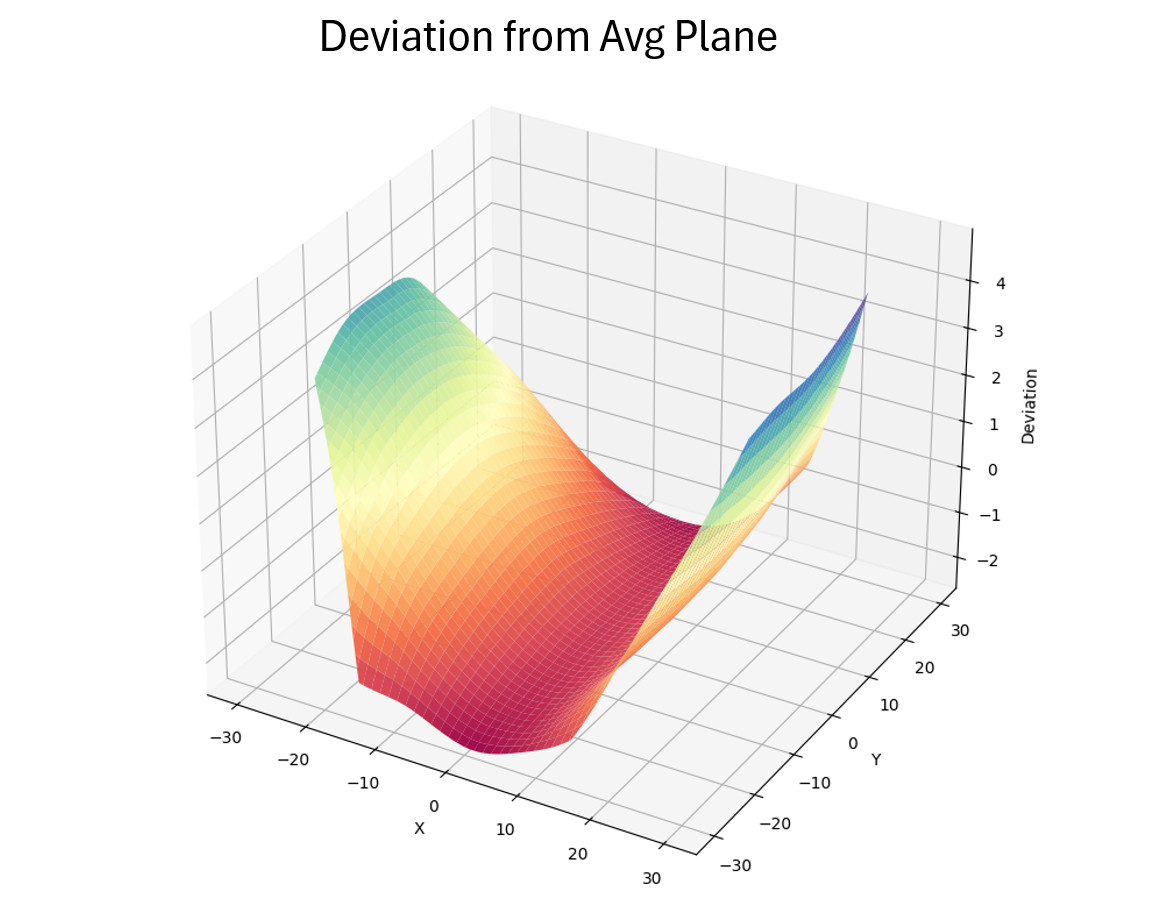

For RMSt, piston and tilt can be removed. To remove them an average plane instead of a line is fitted to the data:

The wavelength deviation of each point to its corresponding point on the average plane is plotted:

Finally, referencing Equation 1 above, the square root of the sum of squares of the deviation is divided by the phase wavelength to yield the final value. Figure 13 shows the result of the grid method applied to the same part as the linear fit model in Figure 8. A more comprehensive tactic makes this approach a more conservative TWE predictor when compared to the empirical interferometric measurement.

Figure 13. On the left: full 2D analytic TWE values obtained using wavelength scans taken at every grid point location shown by the black points. On the right: a single interferometric 2D scan of the same part.

It should be noted that the grid method RMS reported value utilizes interpolation and doesn’t fully match the Zygo fit algorithm since we are fitting a plane versus a set of Zernike coefficients.

Application, Next Steps

This analytical TWE tool is especially powerful from a manufacturing standpoint, where larger aperture optics and tight wavefront specifications often strain conventional metrology and process controls. As component sizes increase and clear apertures exceed 50–100 mm, even small coating thickness gradients can introduce system level aberrations that need to be well understood. By converting routine spectral uniformity measurements into reliable TWE estimates, manufacturers can qualify coating performance earlier in the process, reduce reliance on oversized interferometers, and confidently scale production of large filters, windows, and free space communication optics without introducing metrology bottlenecks.

Looking forward, applying this method to real production components—such as widefield imaging filters or large format solar rejection filters for Free Space Optical Communication (FSOC) systems—allows process engineers to optimize tooling layouts, tuning strategies, and chamber specific deposition profiles with tighter feedback loops. The grid based RMSt approach, in particular, enables detailed spatial mapping that supports root cause analysis for coating nonuniformity and helps guide fixture redesign, rotation schemes, or mask adjustments. As a next step, expanding this work into a manufacturing focused “Gen2” study would demonstrate how predictive TWE modeling can decrease scrap rates, improve coating yield across large parts, and provide a scalable qualification path for high volume production of increasingly demanding optical components.

Conclusion

The predictive modeling approach outlined here leverages the fundamental relationship between coating thickness, spectral position, and phase to accurately estimate TWE in cases where interferometric measurements are impractical or unavailable. Its effectiveness depends on a coating process with exceptionally high deposition accuracy and repeatability—making it particularly well suited to a high-performance platform such as Alluxa’s SIRRUS™ plasma technology. By combining spectral uniformity data with a linear fit and/or grid based spatial analysis, this framework delivers a robust, physics driven method for evaluating and controlling coating induced wavefront error in manufacturing. In turn, it supports tighter process tuning, more efficient chamber utilization, and more reliable qualification of optical filters with demanding TWE specifications—enabling consistent, scalable production of high-performance optical components.

Alluxa Engineering Team

References:

[1] “Field Guide to Optomechanical Design and Analysis.” Schwertz, K., & Burge, J. (2012). SPIE Press: https://doi.org/10.1117/3.934930.ch89